Why I-526 processing time is relevant

February 2, 2020 12 Comments

Another response to the announcement “USCIS Adjusts Process for Managing EB-5 Visa Petition Inventory.” Today’s question: Does timely I-526 processing really benefit, or make a difference, to everyone? What about people from countries facing long visa wait times regardless? Does someone from Vietnam care about getting I-526 approval in 2020, if he can’t expect a visa until 2024 anyway? In fact, shouldn’t he rather wait as long as possible for an I-526 decision, since his children are protected from aging out so long as the petition is pending? Assuming he chose a good project and prepared a solid petition, why care whether the I-526 gets approved early or late?

I argue that processing time is relevant for all petitioners, and that the limited benefit of delay does not outweigh the major drawbacks.

- Extended child status protection is indeed a benefit of extended I-526 processing time for someone with a long visa wait anyway.

- If I’m guessing correctly about how USCIS would implement the “visa availability approach,” and near-term processing volume, USCIS may take about a year longer to adjudicate China and Vietnam I-526 than it would’ve taken under the supposed current FIFO approach. If so, that would add one more year to the time that the dependents of Chinese and Vietnamese petitioners can have their ages frozen. (I’m not contemplating the possibility that USCIS might look at Oppenheim’s visa wait time estimates, and plan to just shelve Chinese I-526 for sixteen years, and Vietnamese I-526 for seven years, regardless of rest-of-world demand. Because that would be crazy, from every angle besides helping child status protection.)

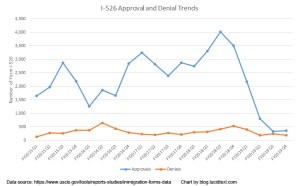

- However, children only benefit if the immigrant petition ultimately succeeds. Delay increases the likelihood that the I-526 may be denied due to circumstances outside the petitioner’s (and often outside the project company’s) control, and the pain of such failure.

- Adjudication timing can affect the adjudication outcome, even for investors in successful projects.

- In a fair world, a petition that’s approvable when it’s filed should still be approvable whenever it’s adjudicated, provided that project problems don’t emerge in the meantime. In practice, USCIS sometimes denies originally approvable petitions in projects that succeed. This happens when USCIS policy interpretations shift between the time of filing and the time of adjudication. At the base of this post, I’ve compiled some specific examples of this happening, when USCIS changed thinking over time about investment structures, source of funds, and evidence requirements. (When USCIS admits a policy change, there’s protection from retroactive application, but this protection doesn’t apply when the shift isn’t officially acknowledged as a change.) Long processing times maximize vulnerability to such interpretation shifts. A petition is most likely to be judged by the standards that prevailed when it was filed if it’s adjudicated somewhere near the time it was filed. That’s a major reason to advocate for timely processing for everyone. People won’t file I-526 if they can’t predict the standards that will apply when the I-526 is adjudicated.

- Timely I-526 adjudication has benefits, even if the visa is not yet available.

- If the petition will be approved, it’s best to get the approval as soon as possible. I-526 approval establishes a priority date, and the protections that come with having a priority date. (For example, grandfathering under existing rules in case of adverse legislative changes.)

- If the petition will be denied, it’s best to get the denial as soon as possible. A prompt denial decision reduces uncertainty, increases transparency, helps to catch and stop frauds, and opens the possibility for investor protections and recourse such as denial-triggered exit strategies and approval-contingent escrows.

- If material changes could happen during the course of the visa wait, it’s best if they happen after I-526 approval. The priority date of the approved I-526 may be retained even if material change necessitates moving investment to a new project, under the priority date retention policy. If the material change happens prior to I-526 approval, there’s no recourse. Also, consular officers are less likely than USCIS to flag changes as material for hypertechnical reasons.

- I-526 processing times can be relevant to visa wait times. For example:

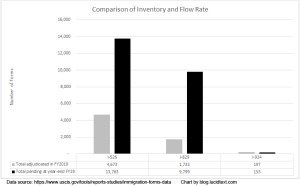

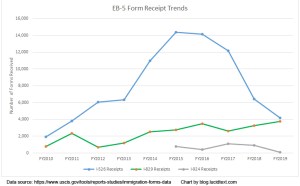

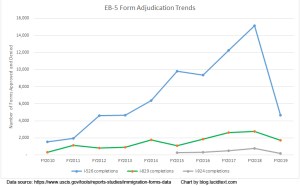

- There were enough I-526 filed in FY2012 to use the full annual EB-5 visa quota. But due to I-526 processing delays, Department of State issued less than the full quota of EB-5 visas in FY2013. Visa numbers went to waste in 2013 because USCIS didn’t move people to the visa stage in time. At recent dismal processing volumes, USCIS will have to hustle to advance sufficient India petitions to maximize annual available visas.

- Charles Oppenheim of Department of State estimated in October 2019 (a) that Indians filing “today” faced a 6.7 year visa wait, and (b) that India could possibly be “current” in the October 2020 visa bulletin. How could (a) and (b) both be true? Answer: if most of the India backlog stays stuck at USCIS, instead of advancing to the visa stage. Currently, I-526 processing is creating the visa bulletin for India, as Department of State moves the Final Action Date depending on how many I-526 approvals for Indians come out of USCIS, and the priority dates on those approvals. The “visa availability approach” concept predicates I-526 processing priority on visa availability. The current India situation shows how visa availability results from I-526 priority. I don’t know whether USCIS has considered how to handle such a Catch 22.

Examples of how I-526 adjudication timing has been relevant even for I-526 with no project problems

Project Documents Examples

- In 2018, IIUSA wrote a letter to USCIS that discussed problems with long processing times, including changing policy interpretations that occur over the course of the wait time. The letter noted that “IIUSA member Regional Centers report an increase in requests for evidence (RFEs) on pending I-526 petitions, even for projects with I-526 and I-924 petitions already approved.” Some RFEs simply requested updated project information, and would have been unnecessary had the I-526 been adjudicated in a timely manner, when its project documents were still up-to-date. Other RFEs suggested that USCIS was applying new internal policy guidelines. For example, bridge financing arrangements that had previously been approved were being held to unpublished new standards regarding the timing and flow of funds. “The lack of consistent adjudication, and the application of policies developed without public input or visibility, applied retroactively, threatens the viability of the entire EB-5 program: How can projects start and investors invest, based on today’s policies, only to find that the projects and investors are adjudicated based on new policies developed while the petitions wait years for adjudication?”

- According to the precedent decision Matter of Izummi (1998), EB-5 applicants who are guaranteed repayment of their capital contributions have not made true investments. Historically, USCIS applied Matter of Izummi to prohibit only arrangements which give an EB-5 investor the contractual right to receive back some or all of her capital contribution. However, in recent years USCIS began denying I-526 based on an interpretation that redemption rights given to the new commercial enterprise are also impermissible. [Kurzban & Pratt] The case Chiayu Chang, et. al., v USCIS concerns six investors who made investment and filed I-526 between December 2013 and September 2014. Their Limited Partnership Agreements included a call option of a kind that had been standard in many EB-5 offerings, and previously been approved by USCIS. The investors received RFEs in July and August 2015 that mentioned no problem with the Limited Partnership Agreement. Then in December 2015, the investors received Notices of Intent to Deny based on the call options in their LPA.

Source of Funds Example: Currency Swap

- Historically, USCIS accepted currency swaps as an acceptable method for transferring funds to the US, and generally did not examine the background of the party providing US dollars in the currency swap. [Hermansky]

- In 2017, for the first time, USCIS started issuing RFEs to Chinese investors who used third party money exchangers to transfer money to the US. [Klasko] No explicit policy change was ever made, but RFEs starting in 2017 indicated that USCIS was changing its policy interpretation and adjudication practice.

- JAN142020_02B7203.pdf is an example of a petitioner who made an EB-5 investment in 2016, using the then-accepted currency swap practice to move funds out of China. The petition was not adjudicated until 2018 or 2019, at which point USCIS applied the new policy interpretation regarding currency swaps, and requested source-of-funds documentation for the third party who facilitated the currency swap. No one knew back in 2016 that such documents might be requested, and the petitioner did not have them in hand. The third party, when approached with USCIS’s belated evidence request, “was not willing to provide any financial documentation due to concerns regarding his privacy and security.” USCIS then denied the petition for insufficient source of funds. The petitioner appealed, claiming “it was unreasonable to request [the third party’s] financial documentation because, at the time of I-526 filing, USCIS did not require a third-party exchanger to provide his or her personal banking, business, and financial records, and it was not anticipated by the [Petitioner], his parents, or the [Petitioner’s] attorney, that such a requirement was forthcoming.” AAO did not accept this argument, and dismissed the appeal. The currency swap issue that did not exist at the time of I-526 filing was the sole basis for denial. If the petition had been adjudicated promptly, based on the policy interpretation and adjudication practice that prevailed at the time of filing, it could have been approved because it had all the evidence then required. And this approval, once made, would not have been revisited later despite new policy interpretations, since source of funds are not an issue at the visa application or I-829 stages.

Source of Funds Example: Indebtedness (fact pattern described in Zhang v. USCIS)

- The EB-5 regulations have long specified that “capital” invested in an enterprise can include indebtedness secured by assets owned by the alien entrepreneur, provided that the investor is personally and primarily liable, and that NCE assets are not used to secure the indebtedness.

- On December 23, 2013, Mr. Huashan Zhang made a $500,000 cash investment in an EB-5 NCE. He obtained the invested cash via a loan from a company that he owns, secured by his undistributed profits held by the company.

- In a stakeholder meeting on April 22, 2015, IPO Deputy Chief Julia Harrison expressed an interpretation of the regulations that, for the first time, introduced a “collateralization test” on the value of assets used to secure cash obtained from third party loans.

- USCIS made a decision on Mr. Zhang’s I-526 on May 28, 2015, and denied the I-526 based on a finding that Mr. Zhang’s loan was not properly secured, as expressed in the collateralization test stated the April 22, 2015 stakeholder meeting.

- In June 2015, Mr. Zhang and another petitioner filed suit in district court on behalf of themselves and all other investors who had filed I-526 prior to 2015, and subsequently denied based solely on the ground that the loan used to obtain the invested cash fails the collateralization test described in the 2015 IPO remarks. They claimed that the 2015 interpretation was erroneous, put out without proper notice and comment, exceeded authority, and wrongly applied to their I-526 filed before the interpretation. The court agreed with them, resulting in the class action decision Zhang v. USCIS, No. 15-cv-995. This decision was issued on November 30, 2018, and subsequently appealed by USCIS on January 28, 2019.

- To review, then, the condition of I-526 filed in 2012/2013 if they had one common factor — investments including cash based on indebtedness – but were adjudicated at different times:

- If the I-526 was adjudicated promptly in 2013/2014, it was probably judged based on policy interpretation at the time of filing. Mr. Zhang’s petition could’ve been approved.

- If the I-526 was adjudicated 2015 to 2018, it faced the collateralization test first defined in 2015. Mr. Zhang’s 2013 petition was denied in 2015 for a factor not applied to earlier adjudications. (The log of AAO appeals include other examples – for example NOV092016_02B7203, a petitioner who invested and filed I-526 in 2012, and was denied based on the 2015 policy interpretation when her case was finally adjudicated in 2016.)

- If the I-526 was adjudicated in December 2018, it could be approved with no limitation from the “collateralization test” thanks to the Zhang v. USCIS

- If the I-526 had still not been adjudicated by January 2019, when USCIS appealed Zhang v. USCIS., it is currently still on hold at USCIS. Whether and when it can eventually be approved or denied depends on the outcome of the appeal.

In summary: timely I-526 processing is important and relevant. Let’s fight for it for everyone!

Other Reactions

Here’s my full agenda for posts in response to the announcement “USCIS Adjusts Process for Managing EB-5 Visa Petition Inventory.”

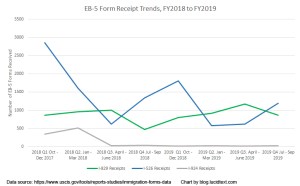

- Argue that when USCIS has proven capacity to give timely processing to all I-526 currently pending, it should not be reducing capacity, necessitating policy to restrict who gets timely processing. [Addressed in last week’s post.]

- Discuss how and why I-526 processing time is relevant even for petitioners from high-volume countries who still face a visa wait following I-526 approval. [This post.]

- Discuss what a visa availability approach could mean for petitioners from low-volume countries, and calculate the potential processing time impact of the change. [Coming later this week.]

- Discuss how and why I-526 processing time makes a practical difference for USCIS, and how delays impact the nature and quality of adjudications. [Coming soon.]

- Define questions that I’d like USCIS to answer regarding how it would implement the visa availability approach. [Coming soon.]

- Discuss the significance of processing times and processing order for businesses that use EB-5 investment. [Not sure if I’ll have time for this, but someone should write it.]

The topic is important, because the viability and integrity of the EB-5 program depend on fair and efficient processing.

Are these posts helpful? If so, please consider making a contribution to support the work.