New Q&A, data, and intel from USCIS and Department of State (I-956 videos, I-829 Q&A, I-485 pending, visa category assignment, source of funds denials)

May 16, 2024 1 Comment

New EB-5 Q&A and I-956, I-956F, I-956G, and I-956K Filing Tips

The EB-5 Resources page on the USCIS website has been updated with the following all-new resources.

- Form I-956 Overview (YouTube)

- Form I-956F Overview (YouTube)

- Form I-956G Overview (YouTube) [This video is currently unavailable.]

- Form I-956K Overview (YouTube)

- EB-5 General Questions and Answers (updated May 2024) (PDF, 287.62 KB)

I most recommend the I-829 questions 6-9 in the EB-5 General Questions and Answers document. This is fresh content, covering questions about how to add eligible derivatives to I-829, reasons for duplicate I-829 receipt notices, how project fraud affects I-829 eligibility, and steps following an I-829 denial. (I gained less from the other May 2024 Q&A, a number of which belatedly respond to outdated questions that IIUSA submitted back in 2020, including Q&A on the now-non-existent I-924A process.) The I-956 form overview Youtube videos are nicely presented, and will be especially useful for those who can’t read the form and instructions. I noted a bit of new content on I-956 supporting evidence and high employment area reporting on I-956F.

Intel on I-829 Adjudication and Source of Funds Denials

USCIS Q&A do not discuss the increasing rate of denials around EB-5 source of funds, but industry has managed to gain inside intel through Freedom of Information Act requests. Ed Ramos’ recent article quotes adjudicator training materials that support my suspicion of an anti-China bias in EB-5 adjudications. Links to related articles:

- Huawei and “The China Threat”: IPO’s New Trend of Denying I-829 Petitions Based on Source of Funds from “Unlawful Entities” (May 16, 2024) by Edward Ramos

- FOIA Documents Shed Light on RFEs and NOIDs Issued by IPO (March 6, 2024) at IIUSA

- Trends and Best Practices in EB-5 Source of Funds – Currency Swaps (May 4, 2023) by John Pratt, Edward Ramos, and Elizabeth Montano

- AIIA FOIA Series: Source of Funds Review at I-829 stage (February 18, 2023) by AIIA

Report of Pending I-485

USCIS continues to regularly update the Employment-Based Adjustment of Status FAQs page, most recently with a response to this important question: “Q. What information is available regarding how many pending Forms I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status, USCIS currently has in its inventory in the employment-based categories by country of chargeability?” USCIS responded with a detailed report of the pending inventory for all EB categories, itemized by country and month/year of priority date. Here is the USCIS report: Form I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status – Pending Applications for Employment-Based Preference Categories. And here is a link to my Excel, with EB-5-specific data from the USCIS report extracted and formatted for analysis.

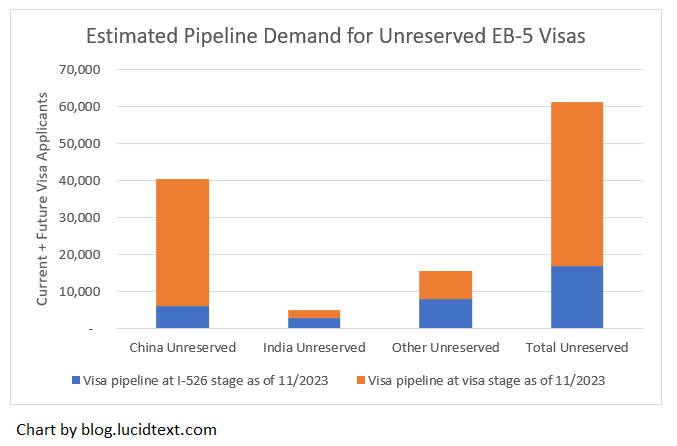

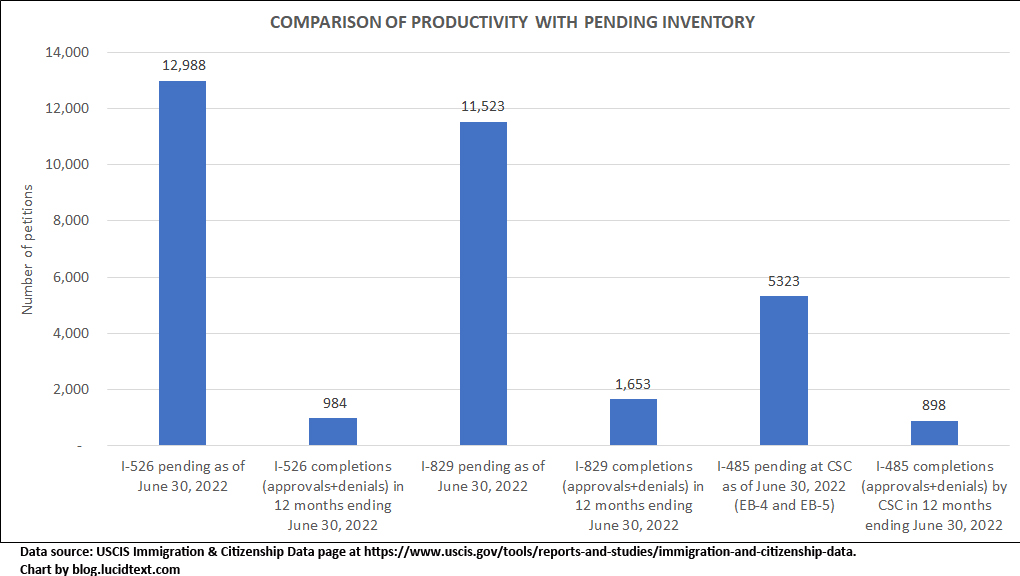

The report is extremely valuable, the first EB-5 I-485 inventory breakdown that USCIS has published since 2019. It is also a bit frustrating to interpret. I wonder why USCIS does not report pending I-485 for the EB-5 reserved categories, though we know that at least hundreds of such I-485 have been concurrently filed since 2022. The data is for Unreserved EB-5 only. USCIS redacts any number <11 with the letter “D,” which means that the EB-5 I-485 inventory total (where “D” appears in 150 fields) could be up to 1,500 higher than the number of forms individually reported. The USCIS report distinguishes between I-485 with and without visas available, but not between I-485 with and without approval of the underlying petition. I don’t know why the total reported EB-5 inventory in this report is so much higher than the number of EB forms reported pending at the California Service Center, which reportedly handles all EB-5 adjustments. All that said, the data is so interesting! We used to ignore pending I-485 when calculating pipeline demand for EB-5 visas, because the number of EB-5 investors using status adjustment vs consular processing used to be so small. But the current crowd of 5,723 to 7,223 people with pending I-485 for unreserved EB-5 is certainly worth counting.

Summary of Pending I-485 Inventory for EB-5 Unreserved Visas as of February 2024

| Priority Date (I-526 filing date) | China | India | All Other Countries | Total Counted EB-5 Unreserved I-485 Pending as of 2/2024 |

| 2014 and earlier | 44+ | 44+ | ||

| 2015 | 815+ | 815+ | ||

| 2016 | 2,059+ | 16+ | 2,075+ | |

| 2017 | 39+ | 39+ | ||

| 2018 | 102+ | 109+ | 211+ | |

| 2019 | 734+ | 1,101+ | 1,835+ | |

| 2020 | 13+ | 13+ | ||

| 2021 | 186+ | 221+ | 407+ | |

| 2022 | 156+ | 115+ | 271+ | |

| 2023 | 13+ | 13+ | ||

| Total Counted EB-5 Unreserved I-485 Pending as of 2/2024 | 2,918+ | 1,178+ | 1,627+ | 5,723+ |

| Maximum I-485 Pending (count plus max sum of every <11 value reported as “D”) | 3,148 | 1,588 | 2,487 | 7,223 |

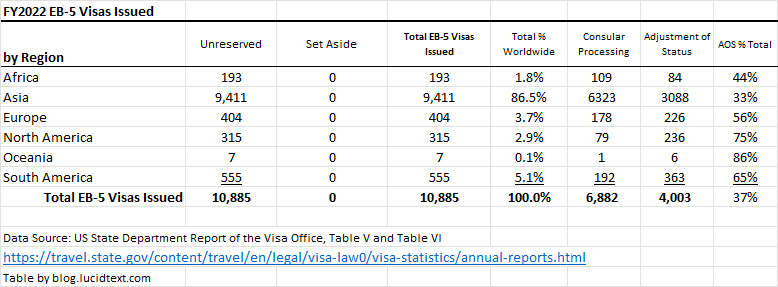

The following table puts the I-485 numbers in context of the most recent reports for other stages of pipeline demand for EB-5 unreserved visas.

| Data Point | A. EB-5 Applicants Registered at National Visa Center | B. Pending EB-5 I-485 at USCIS | C. Pending I-526 at USCIS | ||

| Who’s in this count | investors + family (all with I-526 approval) pre-4/2022 priority dates | investors + family (some do not have I-526 approval yet) pre-4/2022 priority dates | investors only with pre-4/2022 priority dates | ||

| Data as of | as of 11/2023 | as of 2/2024 | as of 12/2023 | as of 3/2022 | |

| Min | Max | ||||

| China | 33,676 | 2,918 | 3,148 | ? | 4,823 |

| India | 1,652 | 1,178 | 1,588 | ? | 2,175 |

| Rest of World | 4,555 | 1,627 | 2,487 | ? | 6,205 |

| Total | 39,883 | 5,723 | 7,223 | 8,539 | 13,203 |

| Total pipeline of unreserved EB-5 visa applicants as of X date for a given country is = A + B + (the portion of C not represented in B, less denials, plus family), adjusted for estimated changes between “data as of” date and X date | |||||

In the above table, you can visualize each row as a queue leading up to a visa window, and each column as capturing a count of people at one stage in the queue. So for example, a Brazilian EB-5 applicant with a 2023 priority date can consult all data points in the “Rest of World” row in the above table to get a sense of the total number of applicants who will be in front of him (based on earlier priority date priority) if he decides to join the Rest of World Unreserved visa queue instead of going for a set-aside visa.

Department of State Q&A on set-aside visa allocation

Data for pipeline demand in the different EB-5 categories is very consequential today, because many post-RIA investors will face a category choice. Many I-526E approval notices give investors the option to join the EB-5 Unreserved queue instead of the Rural or High Unemployment queue for which they also qualify. DOS confirmed this in a Q&A published in minutes from Department of State/AILA Liaison Committee Meeting March 20, 2024.

Can DOS describe the process by which applicants with EB-5 immigrant visa petitions approved with dual Reserved and Unreserved status will be asked to notify the National Visa Center under which processing status they wish to proceed?

Response: Beginning March 21, 2024, IV applicants who USCIS has approved for more than one EB-5 visa classification, reserved or unreserved, will be contacted by NVC and required to select only one of the approved visa classes indicated on their I-797C approval notice and submit their choice using NVC’s online public inquiry form. EB-5 visa applicants will not be scheduled for an interview until they have made a selection. NVC will not select an EB-5 visa class for an applicant. Applicants will be contacted to identify their choice at the Welcome Letter stage. Applicants who have an approved petition and do not receive a notice from NVC should contact us via the online public inquiry form.

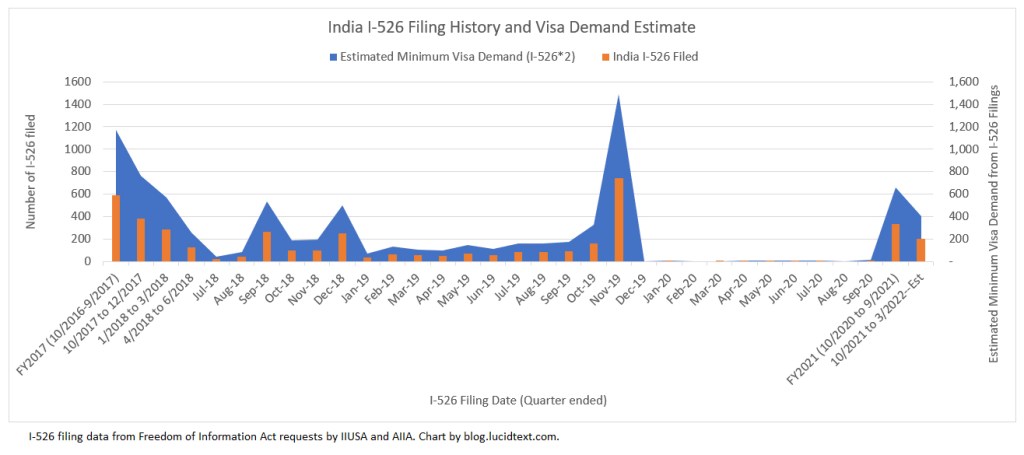

How can EB-5 applicants make the best choice? One wants to choose the category with the least severe demand/supply imbalance. I’ll be writing about this in another post, but in the meantime encourage contemplating the data in the EB-5 Unreserved Pipeline Demand table above, and AIIA’s FOIA data for reserved categories.