Public input to USCIS

May 20, 2021 17 Comments

I’m sharing below a copy of my comment to USCIS, submitted yesterday in response to “Identifying Barriers Across U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Benefits and Services; Request for Public Input.” USCIS asked the public to suggest ways that USCIS “can reduce administrative and other barriers and burdens within its regulations and policies, including those that prevent foreign citizens from easily obtaining access to immigration services and benefits.” Where does one even start? In my comment, I tried to highlight EB-5 problems in context of specific USCIS questions and concerns, while suggesting achievable actions that I judge would help get at the root of those problems. (And I have a long list of other items to discuss shortly in forthcoming articles, as I get time free from business plan work to post more on this blog.)

TO: Tracy Renaud

FROM: Suzanne Lazicki, Lucid Professional Writing

SUBJECT: DHS Docket No. USCIS-2021-0004

DATE: May 19, 2021

1 Assessing Burdens

(2) Are there any USCIS regulations or processes that are not tailored to impose the least burden on society, consistent with achieving the regulatory objectives?

Problem: Are there any USCIS regulations or process from recent years that were tailored to impose the least burden on society? In her July 2019 Statement for the House Judiciary Committee, Sharvani Dalal-Dheini described her experience at USCIS.

Throughout most of my career at USCIS, any time new policies and procedures were being discussed, there was an informal, but almost automatic reflex to sincerely consider the operational impact it would have on adjudications and the overall effect it would have on the budget. … Things changed in 2017 when a new group of political leadership took the reins and were eager to get out new policies at any cost. As new policy measures were being discussed, we were told that “operational concerns don’t matter.” It became clear that operational, legal, and financial concerns were no longer co-equal voices at the table, but rather policy goals and vetting took the favored child status. [1]

Ms. Dalal-Dheini’s testimony gives many specific examples of burdensome policies and procedures initiated under the leadership attitude that “we are not a benefit agency, we are a vetting agency”[2] and “operational concerns don’t matter.” So long as leadership declines to count costs and considers barriers as a value, then burdens and barriers will proliferate.

Solution: Today, I suggest that the single most important change that new USCIS leadership can make is to say at every table: “we administer benefits” and “operational concerns do matter.” When leadership places a priority on efficiency as well as integrity, then specific efficiencies will naturally result. When leadership cares to count operational and financial burdens, then specific burdens will naturally tend to be noticed and reduced where appropriate.

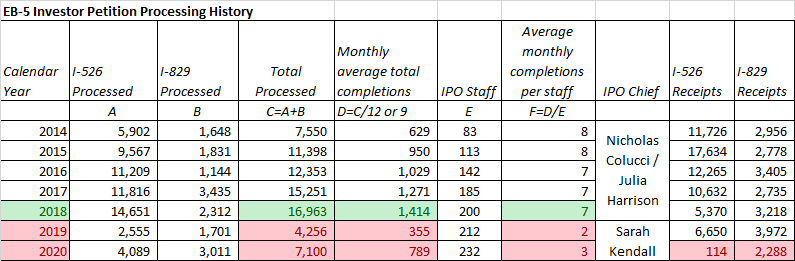

Example with Data: As an example, consider the performance of the USCIS Investor Program Office (IPO), and how productivity rose and fell as a function of leadership priorities.

Table 1. Performance History for EB-5 Forms (I-526 and I-829) at the Investor Program Office[3]

In her first year as IPO Chief, Sarah Kendall succeeded in making the Investor Program Office four times less productive than it had been previously, and processing times ballooned. In her second year, new EB-5 form filings fell to historic lows. Plummeting receipt and adjudication numbers reflect a variety of specific barriers and burdens implemented under her leadership, but fundamentally follow from the basic attitude discussed above — “we are a vetting agency” and “operational concerns don’t matter.” Sarah Kendall repeatedly emphasized during her tenure that “Program integrity is at the forefront of everything we do. IPO is continually fielding questions from Congress and others on performance in this area.”[4] She did not place a value on efficiency, and performance data shows the result. Today, the single best way to reduce barriers and burdens in EB-5 would be to put new leadership in place who will say “Integrity and efficiency are at the forefront of everything we do, and we are continually fielding questions about our operational effectiveness.”

2 Promoting Equity

(3) Are there USCIS regulations or processes that disproportionally burden disadvantaged, vulnerable, or marginalized communities?

Problem: Long USCIS processing times disproportionally harm the most vulnerable. This is obvious in theory: who suffers most from a long wait for a benefit? The one who most needs the benefit. It is also evident in practice.

Take the example of EB-5, where the processing time for I-924 Application for Regional Center has been posted at three to five years. Which kind of project can best afford to wait three years for USCIS review: the wealthy urban project that can proceed with or without EB-5 immigrant investors, or the project in a distressed area that depends on EB-5 to proceed? With unpredictable multi-year processing times for I-924 and I-526, EB-5 can hardly do what Congress intended: promote investment in vulnerable areas, in projects where economic impact and job creation are contingent on EB-5 investment, and thus on EB-5 processing. Instead, long processing times privilege the strongest projects best able to proceed without EB-5 and create jobs regardless of EB-5 delays.

Data Example: To confirm and quantify the disproportionate negative impact of long USCIS processing times in EB-5, USCIS could request the following data from the Investor Program Office: (1) trend in number of direct EB-5 vs. regional center I-526 filings (with direct EB-5 generally involving small business and individual entrepreneurs for whom long processing times present a particular barrier); (2) trend in the number of projects in first tier cities vs. small cities and rural areas (with small areas most dependent on the EB-5 investment and thus the timely processing); and (3) trend in the amount of EB-5 investment used to replace existing financing, rather than directly fund project costs. Anecdotally, I see ballooning EB-5 processing times correlate with a trend toward EB-5 investment seeking the large and fully-funded urban projects best able to weather USCIS processing delays. This pushes EB-5 from a job-creating to a mere capital-cost-reducing program, contradicting Congressional intent for EB-5.

Solution: USCIS should place a value on efficiency and well as integrity, realizing that long processing times are not equitable.

3 Data Sources

(6) Are there existing sources of data that USCIS can use to evaluate the post-promulgation effects of regulations and administrative burdens over time?

a. USCIS should analyze and learn from its own data as reported on the Immigration and Citizenship Data page.[5]

- Receipt data: USCIS should regularly analyze trends in receipts for each Form type. Falling receipts means depressed demand, which likely reflects a barrier or burden. For example, data shows that I-526 receipts fell 98% following implementation of the EB-5 Modernization Regulation in November 2019 (comparing I-526 receipts in the three quarters before and after the regulation took effect). That Form receipt data point is obviously relevant to understanding the impact of the regulation on potential immigrants.

USCIS’s own receipt data is also critical when budgeting for Fee Rules. According to OMB Circular A-25, fees should be set “based upon the best available records of the agency.” But the 2019 Fee Rule relied on estimated “projected workload receipts” dramatically at odds with actual workload receipts as published on the USCIS Citizenship & Immigration Data page. For example, the 2019 Fee Rule had a “projected workload” of 14,000 I-526 receipts for FY2019/2020 even as USCIS had reported barely 5,000 I-526 receipts for FY2018/2019. This resulted in the 2019 Fee Rule massively overestimating future Form I-526 revenue, not to mention failing to account for funds needed to cover the burden of processing the large backlog of pending I-526 from previous years. Such oversights could have been rectified, had USCIS consulted its own data for form receipts and inventory.

- Approval and denial data: USCIS should regularly analyze trends in adjudications (approvals plus denials) for each Form type. Falling adjudication volume reflects falling productivity at USCIS, which flags a barrier. For example, data shows that Investor Program Office productivity was 77% lower in FY2020 than in FY2018 despite staffing increases (comparing the number of approvals and denials of Form I-526, I-829, and I-924 between those fiscal years). That productivity data point flags management problems at IPO, and raises questions about new EB-5 policies and procedures that resulted in making adjudications three to four times more time-consuming than previously.

- RFE data: USCIS should regularly analyze RFE trends for each form type. When an increasing percentage of cases are receiving an RFE, this flags a burden that can then be scrutinized. Educated by data, management can ask: why are more RFEs being issued? Have standards changed, and if so, how? Are the changes reasonable and operationally justifiable? Were the changes announced? Could the situation be improved by clarifying Form instructions or other guidance, so that petitioners know to provide correct and complete information upfront to avoid RFE?

- Cost data: USCIS should examine trends in the amount of money it has spent defending against litigation. When constituents resort to suing USCIS, this signals frustration levels with barriers and burdens that need to be addressed. It also invites management reflection about how funds might be better used to address problems before they become lawsuits. For example, USCIS could reduce Mandamus litigation significantly by the simple expedient of improving the USCIS Processing Times Report. A confusing and misleading methodology and obviously unreasonable “case inquiry date” on the Processing Times Report create needless frustration and attracts lawsuits.

- Data reporting: To the end of making its own data useful for management, USCIS should improve its data collection and reporting. The “All Forms Report” on the USCIS Immigration and Citizenship Data page may take the prize for Worst Data Presentation of All Time. The report makes every data point impossible to read without a magnifying glass, omits historical data needed to identify trends, and stymies Form-specific analysis. And yet this report is the only data source for many USCIS forms. Even Excel could take minutes to generate individual reports of USCIS form data, if USCIS valued data transparency and data-based oversight enough to generate readable and actionable reports.

b. USCIS should attend to existing public feedback about USCIS operations.

- I recommend USCIS to review testimony presented at the House Judiciary Committee Hearing on “Policy Changes and Processing Delays at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services” held on July 16, 2019.[6] This hearing gathered detailed feedback from a wide array of constituencies on specific barriers and inefficiencies at USCIS, specific costs associated with those barriers, and suggested solutions. It is not clear that USCIS noted or responded to any of the excellent input offered at this hearing.

- I recommend USCIS to review public comments made in response to USCIS Policy Manual updates.[7] We the public put great effort into providing detailed feedback on the practical impacts of policy changes, and no one even reads the Policy Manual feedback so far as we can tell.[8]

- I recommend USCIS to review input provided to the CIS Ombudsman. The Ombudsman and the public expend considerable effort to identify and diagnose performance problems, and then USCIS does not respond.[9]

4 Form I-526 Inconsistency

Problem: The evidence requested in the Form I-526 and Form I-526 Instructions does not align with evidence checklists provided to adjudicators who review Form I-526. This inconsistency is evident to the public from (1) Requests for Evidence, which routinely quote standardized evidence lists not included in the Form I-526 or I-526 Instructions, and (2) materials from “Immigrant Investor Program Office Training May 8, 2019” (obtained via FOIA request) which instruct adjudicators to request evidence that the Form I-526 and Instructions do not request.

For example: no public-facing guidance requests I-526 petitioners to prepare source of funds documentation for non-EB-5 investors in the New Commercial Enterprise. This category of evidence is not mentioned in the Form I-526 Instructions, not in the Form I-526 Filing Tips or Suggested Order of Documentation for I-526 published on the USCIS website. The EB-5 regulations could justify requesting this category of evidence, but in practice USCIS evidence collection documents and guidance do not request it. (Possibly, because it’s obviously unreasonable to ask a petitioner to prove the source of funds for unrelated third parties who happen to have invested in the same project, and are not seeking immigration benefits.) But if an unreasonable information request exists, it should at least be published. No one benefits from lack of transparency upfront about required evidence. Petitioners cannot know to prepare evidence that USCIS does not request.

Solution: The May 2019 IPO Training discloses the existence of the following three internal “adjudication worksheets,” each of which is accompanied by an “instructional guide”: Form I-526 Worksheet; EB-5 Project Review Worksheet; Form I-526 Deference Worksheet. USCIS should review the content of those adjudicator worksheets and instructional guides, and identify discrepancies with the public I-526 Instructions, Filing Tips, and Suggested Order of Documentation. Then revise the internal and/or the public guidance and instructions as needed so that everyone is on the same page about what is required for I-526 adjudication.

5 Form I-924 Inefficiency

Problem: Form I-924 is problematic because it uses a single form, single fee, and single processing workflow for a variety of applications that are entirely different in their workload and processing needs: initial application regional center application; request for project review; required regional center amendment; optional regional center amendment. Regional centers are discouraged from sending optional updates to USCIS (e.g. new contact information) because such updates use the same form and thus involve the same $17,795 fee as a labor-intensive new application. Regional centers are discouraged from getting optional project review from USCIS – a step that’s extremely valuable for program integrity – because that project approval uses the same form and thus promises the same deadly 3-5-year processing time as an initial application.

Solution: Create separate forms, fees, and processing workflows for the separate processes currently combined in Form I-924.

6 Data Reporting: Country-Specific Demand Data

Problem: USCIS does not report country-specific demand data for numerically limited categories (i.e. receipt data for petitions in categories with limited visa availability).

Specific example of why this is a problem: EB-5 is a numerically limited category subject to country caps, with future backlogs and visa waits created by the number of people by country who start the process by filing Form I-526. Thus, preparing for backlogs and wait times requires data for the number of I-526 receipts by country. USCIS regularly collects and reports this data to Department of State for planning purposes, but has persistently not only neglected to but positively refused to share such data with the public. I-526 receipt data by country is not published on the USCIS Immigration and Citizenship Date Page. Furthermore, the Investor Program Office Customer Service has repeatedly declined to respond to public inquiries requesting this information[10], Freedom of Information Act Request soliciting this information have gone unanswered[11], and the one country-specific I-526 inventory report briefly provided by USCIS was subsequently deleted from the website[12].

Lacking visibility into I-526 receipt numbers by country, businesses and prospective EB-5 immigrants cannot predict or plan to avoid future backlogs and excessive visa wait times. The public is left with no visa backlog signal except the visa bulletin (which reports on past visa wait times rather than signaling future wait times), and periodic non-public industry event presentations from Department of State.

Lack of country-specific I-526 data reporting led to the quiet buildup of a decade-long EB-5 visa backlog before China-born prospective immigrants became aware of the problem, and were empowered to choose to avoid it. [13] This unfortunate history promises to repeat today for India, whose EB-5 backlog situation may be severe but is not yet publicized. U.S. businesses today are still recruiting EB-5 investor applicants from India and making business plans assuming a five-year investment horizon, looking at the Current visa bulletin. They are unable to account for the number of India I-526 filed with and pending at USCIS, because USCIS refuses to publish this information. This lack of transparency from USCIS is a major integrity problem and needless process barrier.

Solution (EB-5 example): Start publishing these two data reports regularly on the USCIS Immigration and Citizenship Data Page:

- Essential: quarterly I-526 receipts country (top 8 countries + rest of world)

- Ideally also: I-526 pending inventory itemized by country (top 8 countries + rest of world) and by month or quarter of filing date

Alternatively or additionally, publish the I-526 data report that the USCIS Investor Program Office already generates monthly and provides privately to Charles Oppenheim of Department of State for visa bulletin reference.

Publishing demand information will help to prevent pileup of expensive and painful backlogs by educating the public and facilitating self-regulation. Publishing visa demand data would conform to the project management best practice to “elevate the constraint” with respect to the visa limits that constrain immigration processes.

7 Data Reporting: USCIS Processing Times Report

Problem: The USCIS Processing Time Report[14] is confusing and creates costly frustration. It reports an “estimated time range” for each form, where the first month represents the median age of recently-adjudicated cases, and the second month represents the age of extreme outliers in recent adjudications (the 7% oldest cases)[15]. The second number – the age of extreme outliers – is then used to calculate a “case inquiry date” which limits who can use normal channels to inquire about case status. According to the stated method, only the low month in the “estimated time range” represents something like normal processing – i.e. the median age of recent adjudications. And yet, the report stipulates a case has to be older than 93% of cases recently adjudicated before the petitioner can even make a case inquiry.

Example of why this is a problem: According to the current USCIS Processing Times Report, the median processing time for recent non-China I-526 adjudications is less than 31 months, and yet a given petition cannot be considered “delayed” or make an inquiry unless it has waited over 49.5 months for adjudication. In April 2021, I-829 had a “case inquiry date” in the year 2000, meaning that no I-829 petitioner could even inquire about status unless he or she had already been waiting over 20 years for I-829 adjudication. These metrics are too-obviously unreasonable, create frustration, and lead petitioners who have above-average wait times yet barred from ordinary inquiries to jump to costly litigation. In EB-5, Mandamus litigation has become “the new normal”[16], creating needless expense for immigrants and USCIS.

Solution: Revise the USCIS Processing Times Report to calculate the “Case Inquiry Date” from the low end (median) rather than the high end (extreme outliers) of the “Estimated Time Range.” This will allow for reasonable inquiries, short of litigation.

To make the USCIS Processing Time Report less misleading, report an average as well as a median processing time.

[1] Statement of Sharvani Dalal-Dheini Director, Government Relations for the American Immigration Lawyers Association Submitted to the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship “Oversight of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services” July 29, 2020, available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/JU/JU01/20190716/109787/HHRG-116-JU01-Wstate-LindtM-20190716.pdf

[2] Louise Radnofsky, Ken Cuccinelli Takes Reins of Immigration Agency With Focus on Migrant Vetting, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, July 6, 2019, available athttps://www.wsj.com/articles/ken-cuccinelli-takes-reins-of-immigration-agency-with-focus-on-migrant-vetting-11562410802

[3] Data for I-526 and I-829 receipts and processed (approvals plus denials) from the USCIS Immigration and Citizenship Data page. Reported numbers of IPO staff from EB-5 stakeholder meetings and Congressional testimony.

[4] https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/outreach-engagements/IIUSA_2020_Virtual_EB-5_Industry_Forum-IPO_Chief_Sarah_Kendalls_remarks.pdf

[5] https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-and-studies/immigration-and-citizenship-data

[6] https://judiciary.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=2273

[7] https://www.uscis.gov/outreach/feedback-opportunities/policy-manual-for-comment

[8] For example, see IIUSA’s “Comments on USCIS Policy Manual, Vol. 6, Part G, Chapters 2 and 4,” submitted through the USCIS Policy Manual Feedback process and also available at https://iiusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IIUSA-AILA-Comments-on-Deployment-of-Funds-to-USCIS_8.23.2020.pdf

[9] For example, consider IIUSA’s “EB-5 Industry Comments, Questions, and Concerns for IIUSA Meeting with CIS Ombudsman Office on Tuesday, February 2, 2021” submitted to the CIS Ombudsman, and also available at https://iiusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IIUSA-Comments-for-CIS-Meeting_2.2.21.pdf

[10] For example, this document copies my email correspondence with IPO customer service (uscis.immigrantinvestorprogram@uscis.dhs.gov) on this topic from January 2020 to March 2020 https://www.dropbox.com/s/jrvykh6l8grdgqo/IPOemail.docx?dl=0

[11] For example, I have been waiting for over a year so far for response to my FOIA request COW2020000203 submitted in March 2020 for country-specific I-526 data. EB-5 industry trade association IIUSA has made many FOIA requests for country-specific I-526 data that are still pending – for over three years, in some cases. https://iiusa.org/blog/iiusa-foia-information-court/

[12] One extremely helpful data report posted on 10/24/2018 at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Working%20in%20the%20US/i526list.pdf was deleted by USCIS, and now only saved in my folder https://www.dropbox.com/s/zxkmwye1yr1100t/i526list.pdf?dl=0

[13] Excess volume of I-526 filings from China apparently began in 2013, but not well-known until 2017 with the publication of the CIS Ombudsman Annual Report 2017, which reported that Chinese nationals “will likely wait 10 years or longer for their EB-5 immigrant visas due to oversubscription.” The China EB-5 market then regulated itself after 2017, thanks to this education, but too late for thousands of U.S. businesses and investors who had already made investment decisions in ignorance of decade-long wait times resulted from un-reported country-specific usage.

[14] https://egov.uscis.gov/processing-times/

[15] https://egov.uscis.gov/processing-times/more-info

[16] “EB-5 litigation: The new norm for EB-5 investors” By Bernard Wolfsdorf in EB5 Investors Magazine (April 1, 2021) https://www.eb5investors.com/magazine/article/eb5-investor-litigation

Discover more from EB-5 Updates

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi Suzzane.

Congratulations on your Public Comment posted at the

“Identifying Barriers Across U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services” request for public input.

This was a major opportunity to let USCIS know the areas in which they definitely have to improve.

All of your comments are very detailed and really focused in the areas they need to work on. Very well done!!

Hope it is for the best.

I invite everyone who thinks the comments are good to support this blog by making a donation to Suzzane.

You can find the link to make a donation via PayPal on the top-right part of this blog, right below her phone number.

You are too kind! Really appreciate your support.

Hi Suzanne, great work. Was wondering if you have any updates on what’s happening with the reautherization of the regional center program? Any updates would be greatly appreciated. Thanks

It’s so complicated that I hardly know what to say. I will write more soon, but in the meantime you might join an advocacy group to get more realtime updates and discussion.

What group is this abs how can one join?

Excellent, thoughtful and well-argued response. Thank you so much, Suzanne!

Hi Suzanne thank you for brilliant analysis.I enjoy reading your work . It keeps me informed and updated

Thanks for your great job! That is very helpful for us to understand what is going on! thanks again

Hi Suzanne,

How long does USCIS takes to transfer the case to NVC now a days? My petition (India) was approved on December 20. It has already been more then 5 months and USCIS still hasn’t transferred my case to NVC. I already did bunch of inquiries with NVC as well as USCIS but it seems they pretty much ignore this kind of inquiries with standard answer. Thanks.

Either you or your lawyer (the latter is probably better) should write NVC attaching a scan of the form I-797 USCIS sent you (this is important).

I was in a similar situation, my I-526 was approved on November 20th. In February, I sent an email on my own, and received a standard response. Then I had my lawyer write them, and he attached a copy of the I-797 to the inquiry. That apparently did the trick: they replied that they would contact USCIS and request the file from them. Ten days later, NVC notified us they had created a case file.

I imagine that everyone on this blog can relate to you. I also feel frustrated. Congratulations on the approval and I hope your case moves forward quickly.

Thank you Roberto for sharing your experience! Very helpful. Meg, note also p. 16 and following of these meeting notes: https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/AILA/AILA-NVC-meeting-02-17-2021.pdf DOS told AILA that “During CY 2020, the median time for an approved I-526 petition to reach NVC was 126 days.”

Thank you Suzanne, Roberto and Other members for insights. It indeed is very helpful!

Suzanne – My father has a very serious medical condition which requires 4 to 5 hours treatment in medical facility 3 days a week. My visa delay is taking a huge toll on all of us as a family because of his frail situation. He is a US Permanent resident and it would be a huge help for him physically and emotionally if me being with him coping with his situation. Does this stand for medical ground to expedite the process at NVC and Visa interview. Thank you.

Sounds worth a try to me, but your lawyer can give the best advice on this. If I were the decision-maker, I would be moved by this story.

Congratulation You will soon hear from them as it took same time for my friend can you tell the priority date

Thanks. Priority date APRIL2017. It was a long and frustrating journey really and still waiting…

Congratulations Again I hope you will hear from them soon Good Luck