Impact of Reserved Visas in the EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022 (analogy, law, data, application, Oppenheim comments)

April 3, 2022 16 Comments

Introduction

This post tackles a momentous question: what is the impact of the 32% reserved visas provision in the EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022?

In the zero-sum visa game, newly-reserving visas for some means newly-restricting visa availability for others. That’s self-evident. But who wins and loses, and how much?

I’ll start with my conclusions, then take a deep dive into the detail, calculations, and questions behind the conclusions.

- Reserved visas will probably not harm pending EB-5 applicants from countries other than China, Vietnam, and India, because country caps still protect minority-country visa availability, and demand under per-country limits has always been well under 68% of the annual EB-5 quota.

- Reserved visas also have no incentive value for incoming EB-5 applicants from low-demand countries, since these applicants already have visa availability protected by country caps, and no visa backlogs to avoid.

- Reserved visas can have incentive value for incoming EB-5 applicants from high-demand countries with backlogs (China, Vietnam, India) provided that the reserve visas are exclusive to incoming applicants, and thus offer a way to avoid standing in line behind thousands of pending applicants with earlier priority dates.

- Reserved visas have a devastating cost for pending China-born applicants, because reserved visas drain the pool of “otherwise unused” numbers normally generally available at the end of every year to applicants with the oldest priority dates. The magnitude of the negative impact depends on whether or not Department of State interprets and applies the new law as making all reserve visas practically exclusive to post-March 15, 2022 priority dates, and thus inaccessible to the 80,000+ pending EB-5 applicants already queued up for visas. [6/21/2022 Update: DOS has announced that it interprets reserve visas as only available to applicants who file I-526 after March 15, 2022, and unavailable to the backlog.] But even with optimal interpretation, the China backlog is poised to lose access to at least 2,000 visas a year.

This article has five parts:

- Analogy: To set the stage, I suggest the analogy of an airport (like EB-5, a multi-stage process), and passengers waiting on standby (analogous to oversubscribed EB-5 applicants waiting on unused visas).

- Law: I list out all the provisions in existing law that govern EB-5 visa availability, and the specific changes made in the EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022. This exercise highlights ambiguities and room for interpretation. I transcribe comments on the ambiguities from Charles Oppenheim, recently retired from Department of State, at a March 22 webinar with Wolfsdorf Law.

- Data: I lay out data for historical EB-5 visa demand, supply, and allocation.

- Application: I review how EB-5 visa wait time estimates worked under the old law, and consider the marginal impact of the new law on visa supply and wait times.

- Conclusion: I consider possibilities for making the reserve visas law turn out less bad for our past clients than it could be

(This post replaces my previous analysis in opposition to set-aside visas in March 2018, May 17, 2019, May 21, 2019, May 2021, and Sept. 2021.).

Part 1: Analogy

| Airport Analogy | EB-5 Parallel |

| Three stages: buy a ticket, wait in the security queue to get to the gate area; wait in the gate area to get on a flight. Only passengers who reach the gate area are practically as well as theoretically eligible to use their tickets to get seats on a flight. | File I-526, wait for I-526 processing, then wait in the consular or adjustment process for a visa. An I-526 priority date is a kind of ticket to maybe claim a visa in the future, but only people who are documentarily qualified at the visa stage can use their priority dates to claim visas. |

| Standby tickets: Flying standby means that my ticket doesn’t lock in a specific designated seat, but I still have a chance to get a seat — assuming that a flight will have enough undesignated seats leftover for standbys to take. | Most EB-5 applicants from China are waiting on standby status for visas. Most Chinese do not have designated places in the annual EB-5 visa quota thanks to overbooking (under country caps, only 7% of annual visas can go to any one country by right). But having the oldest priority dates, Chinese are at the front of the standby line for any annual visas left unclaimed after by-right per-country allocations. Historically, at least over 40% of annual EB-5 visas have been “otherwise unused” and therefore leftover for the standby queue. Chinese have been able to depend on flying standby, because (1) they’ve been waiting longest and therefore at the head of the standby queue, and (2) a good number of “otherwise unused” visas have been reliably available to standby given the inherently low EB-5 demand from most other countries in the world. (Vietnam and India, while also overbooked, have not been able to expect any visas over the per-country limit, because they’re more recent and thus behind tens of thousands of Chinese in the standby queue.) |

I believe that in real life, an airline will try to fill a flight with whoever at the gate can board, with people registered on the standby list getting otherwise unused seats in first come first served order.

Imagine if an agent at a crowded gate suddenly announced that 32% of seats on the flight are now exclusively reserved for passengers with codes that don’t yet exist in the boarding area or current standby list, but can be sold on tickets outside to prospective passengers who had been deterred by the long standby queue already at the gate. That’s the closest analogy I can think of to the 32% reserved visa provision in the new law (and particularly the 20% rural reserve, given very few past rural investments).

In the picture, I tried to illustrate who’s happy (the ticket seller), who’s sad (the displaced standby passengers at the gate), who’s confused (the pending standby passengers who technically match reserve conditions, but not sure yet how/if they can claim new codes only being stamped outside on new tickets), who doesn’t care (the passenger who has a designated seat anyway and not dependent on standby or reserves), who’s frustrated (the guy at the gate who looks around, sees no one positioned yet to use up the reserved seats, and realizes that planes will have to take off partly empty until new reserve-eligible passengers finally make it to the gate, meaning existing standbys get further delayed for nothing), who’s conflicted (the prospective passengers standing in a crowd outside the ticket counter, wondering how to interpret the pitch that they won’t find themselves stuck in a crowd once they get to the boarding gate), and who’s two-faced (the airline, with different messages at the ticket counter and the gate).

Part 2: Law

The EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022 introduces two changes to the law for EB-5 visa allocation:

- it repeals/replaces the two pre-existing categories of EB-5 set-aside visas (3,000 regional center, 3,000 TEA), and adds three newly-defined reserved visa categories (20% rural, 10% high unemployment, 2% infrastructure);

- it introduces an instruction to preserve unused reserved visas from year to year within the EB-5 category (without, however, repealing or amending the parts of the existing law that define/cap the annual EB-5 limit and allocate any used EB-5 visas to other visa categories).

| Law prior to the EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022 | Specific changes made by the EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022 |

| INA 201(d): The Employment-Based category is allocated a base 140,000 visa annually. The EB limit for a given year is the base 140,000 plus any unused Family-Based visas from the previous year. | RIA specifies no change to INA 201(d) |

| INA 203(b)(5)(A) Each year, the EB-5 category is allocated a maximum of 7.1% of the EB limit for that year. | RIA specifies no change to INA 203(b)(5)(A) |

| INA 203(e)(1) Available EB visas are generally issued to eligible immigrants in the order in which the immigrant petition was filed. | RIA specifies no change to INA 203(e)(1) |

| INA 202(a)(2) states a per-country limit: that no more than 7 percent of visas available within an EB category in a fiscal year can be made available to natives of any one country. INA 202(a)(3) and (5)(A) provide an exception: that EB immigrants are not subject to the per country limit allocation in a period where available visas exceed the number of qualified applicants to take them. | RIA specifies no change INA 202(a) |

| INA 203(b)(1) If visas still remain unused within the EB-5 category near the end of a fiscal year, such unused visas are made available for use by priority workers (EB-1/EB-2) | RIA specifies no change to INA 203(b)(1) |

| INA 201(c): If the EB category as a whole does not use all its allocated visas in a fiscal year, such unused visas are made available within the Family-Based category in the next fiscal year. | RIA specifies no change to INA 201(c) |

| I’m not sure where this is in the INA, but DOS explains in its document on Operation of the Numerical Control Process that DOS allots visa numbers monthly to consular posts and CIS to be given to reported documentarily-qualified applicants within established cut-off dates. Significantly, visa numbers do not get allotted to applicants earlier in the process; including not when petitioners invest or file I-526. | RIA specifies no change to the timing of visa allotment. |

| Section 610 of the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1993 (8 U.S.C. 1153 note) sets aside 3,000 visas annually for regional center applicants. | RIA Section 103(a) repeals Section 610 of the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1993 (8 U.S.C. 1153 note), thus doing away with the regional center visa set aside in that section. RIA Section 103(b) says that “visas under this subparagraph shall be made available” to a new program for pooled investment, but does not specify a specific number of visas to be made available specific to regional center applicants. |

| INA Section 203(b)(5)(B) specifies that “Not less than 3,000 of [EB-5] visas made available in each fiscal year shall be reserved for qualified immigrants who invest in a new commercial enterprise … which will create employment in a targeted employment area.” | RIA Section 102(a) (2) “amends” (i.e. apparently deletes and replaces) the old INA Section 203(b)(5)(B) to read as follows: “(B) DESIGNATIONS AND RESERVED VISAS.— “(i) RESERVED VISAS.— “(I) IN GENERAL. —Of the visas made available under this paragraph in each fiscal year— “(aa) 20 percent shall be reserved for qualified immigrants who invest in a rural area; “(bb) 10 percent shall be reserved for qualified immigrants who invest in an area designated by the Secretary of Homeland Security under clause (ii) as a high unemployment area; and “(cc) 2 percent shall be reserved for qualified immigrants who invest in infrastructure projects. “(II) UNUSED VISAS.— “(aa) CARRYOVER.—At the end of each fiscal year, any unused visas reserved for qualified immigrants investing in each of the categories described in items (aa) through (cc) of subclause (I) shall remain available within the same category for the immediately succeeding fiscal year. “(bb) GENERAL AVAILABILITY.—Visas described in items (aa) through (cc) of subclause (I) that are not issued by the end of the succeeding fiscal year referred to in item (aa) shall be made available to qualified immigrants described under subparagraph (A). ERIA Section 102 has an effective date of March 15, 2022. |

Notes on what did and didn’t change in the law, and what’s ambiguous

Minority Country Protection: The new law does not change the rule that protects low-volume countries with an annual 7% per country limit – a cap that high-volume countries may only exceed if and when there’s insufficient demand for available visas. Even if the new law does make 32% of 10,000 annual EB-5 visas practically unavailable to the backlog of pending applicants, that shouldn’t hurt minority countries in theory. An EB-5 applicant from Ireland doesn’t depend on a total 10,000 visas available anyway, but only on one of the 7% of EB-5 visas that must be made available to the few Irish applicants ready to claim them before other countries can start to exceed their 7% caps. Thus far, the highest that EB-5 demand under per-country limits has ever gone is 5,851 total in FY2019 (other visas that year were “otherwise unused” and thus issued to the oldest Chinese applicants). So even reducing generally-available EB-5 visas to about 6,800, if set asides have that effect, may not threaten applicants under per-country limits. At the same time, reserved visas don’t stand to benefit minority countries, since applicants from low-demand countries don’t have visa backlogs/visa wait times to avoid.

Eliminating RC and TEA Visa Set-asides: The new law explicitly repeals or replaces the EB-5 visa set asides in previous law: 3,000 for regional centers and 3,000 for TEA. Those set-asides were popularly forgotten because they hardly mattered in practice. There never were over 7,000 non-regional center or over 7,000 non-TEA investors ready to request visas in a year, and thus no one ever ran up against the old set-aside limits. With the backlog dominated by RC and TEA investors, the previous RC and TEA set-asides gave no short-cut around the backlog. So, who cares about eliminating those insignificant set-asides? At minimum, pending applicants are confused now, since their pending applications and the Visa Bulletin are marked for visa codes (C5, T5, I5, or R5) that correspond to the now-eliminated reserved visa categories. The reserve categories around which they invested have suddenly disappeared. For applicants not dependent on the Visa Bulletin anyway, this records confusion shouldn’t affect their actual visa availability. But it’s a reminder that the grandfathering fight is not done; we need to improve the law so that filing I-526 locks in something for future visa availability, not just regional center status. As it is, the law and situation that exists when you commit to the EB-5 process guarantees nothing for visa availability; people are dependent on the visas that exist and the rules for allocating them once they finally reach the visa stage. If the law changes midstream, too bad.

Creating New Reserved Visa Categories: The new law creates three new EB-5 set-aside categories: 20% rural, 10% DHS-designated high unemployment, and 2% infrastructure. These changes are effective as of the date of enactment — March 15, 2022 – which means that someone filing I-526 today should be assigned a new code that marks him or her as belonging or not to one or more of the three new categories. What’s not clear: are any of those these reserved visas theoretically or practically available to the 80,000+ people in the EB-5 visa backlog, who are coded C5, T5, I5, and R5 under the now-abolished RC and TEA set-aside categories? [6/21/2022 Update: DOS has announced that it interprets reserve visas as only available to applicants who file I-526 after March 15, 2022, and unavailable to the backlog.]

In fact, most of the backlog invested in TEAs based on high unemployment. Whether or not those applicants can touch the new 10% high-unemployment set-aside would depend on (1) whether or not DOS interprets the new set-asides as theoretically available to people who started the process pre-enactment and under slightly different high-unemployment area definitions, and (2) whether or not DOS can get USCIS to go back and re-code all the backlogged TEA applicants as being either high unemployment or rural investors, such that DOS is practically able to offer reserve visas to the backlog as well as to new investors.

Of course, the people who drafted the reserved visa law must have wanted the reserve visas available to incentivize new investment. Reserved visas can only have an incentive function if they can offer a priority/timing advantage to new investors, which is only possible if the visas are not absorbed by the many people already in the backlog waiting for visas. Thus the talking point that reserved visas should only apply “prospectively.” This has long been an industry lobbying focus (e.g. this 2019 industry letter to Congress requesting set-asides that apply only to new I-526 petitions and not pending applicants.)

Of course, pending applicants do not want reserved visas to be prospectively available only to incoming I-526. The China backlog must particularly fight to lose as few visa numbers as possible, which means keeping their access to reserve visas if possible. At least, the backlog has a potential chance to access the 10% of visas newly reserved for high unemployment investment. Many backlogged applicants in fact invested in high-unemployment areas, and just need to be re-coded and recognized as such – something for investor associations to fight for. The 20% rural set-aside is probably largely an inevitable loss to the backlog because, as a practical matter, few past investments were in rural projects. Most rural reserves are therefore effectively off the table for the backlog even if DOS decides that past rural applicants could theoretically qualify for rural reserves.

On March 22, Bernard Wolfsdorf and Joseph Barnett held a wonderful webinar with special guest Charles Oppenheim, recently retired chief of Visa Control at Department of State. A webinar recording is now available on Youtube, and I’ve transcribed below a few of Charlie’s comments on the reserved visas provision in the new law.

[Quoted from minute 32] Oppenheim: I do believe that the State Department will have to have new visa categories, and issuance codes or issuance symbols need to be established to identify the applicants who are going to be eligible for processing under the 10, 20, and 2 percent set aside limits. This may actually eventually result in there being five EB-5 visa listings in the visa bulletin. Right now there are only two for non-regional centers and regional centers. Again, with the establishment of new codes to cover the set-asides, I think that is likely to go to five listings.

[Quoted from minute 40] Oppenheim: It’s important to note that the use of the use of the new codes to distinguish the 20, 10, 2 set-asides is going to be necessary for Department of State to compare the amount of numbers which have already been used in those categories, the amount of documentarily complete demand ready for immediate processing, and to know the potential demand requiring use of a number in the future. That information is used not only for the set-asides, but for the determination of any of the preference category’s final action dates. And it’s necessary to apply that to control number use under the respective limits. Therefore it is going to be very important for the officers to know which of the visa codes to be used for final action on a case so that the number use can be accurately tracked and then reported to the visa office for numerical control purposes. Unfortunately my previous position did not require me to know the detailed information which is included on these petitions, so I can’t really say how easy it’s going to be for them to make that distinction between the rural and high unemployment applicants for these set asides.

[Quoted from 1:01:36] Question: Do the reserved visa categories create even longer delays for Mainland China, with the fact that 3,200 visas are being pulled from the general category? Oppenheim: I think there is the potential for that. Although, it’s unknown how many of the Chinese applicants that are in line may be able to benefit by this new set-aside. I think that is one of the unknowns at this point, and I don’t think it’s worth worrying about too much until we know in terms of the official determination of the implementation of the set-asides. [end Oppenheim quote]

Impact of Reserved Categories: If the reserved visas are genuinely reserved for post-enactment I-526, not available to the pending backlog, who wins? In the near term, reserved visas benefit incoming applicants from oversubscribed countries, who would otherwise be stuck in line behind many thousands of fellow-countrymen for generally available visas.

The new law creates visa reserves that work if they restrict 32% of visas such that those visas can’t be issued to the oldest priority dates, and must be issued to post-2022 priority dates or go unused. For example, in 2023 Department of State will have about 2,000+ visas restricted for rural investment. If Department of State has already issued 700 visas to the oldest applicants from every country in 2023 and sees 1,000 rural set-asides still lying unused on the table, it will have to start waving up whichever remaining rural applicants are eligible for those visas, even if they’re Indians or Vietnamese or Chinese already over the 700 limit and with priority dates far more recent than their backlogged fellow-countrymen. That’s the queue-cutting opportunity. Genuinely reserved visas serve to create a new category of standby that can attract new applicants from China, Vietnam, and India who would’ve otherwise been at the back of the old generally-available standby queue. I emphasize “near-term” advantage for in-coming applicants, though, because a new standby category only benefits the people who start the new queue. 2,000 rural visas per year can sustainably accommodate around 700 investors per year, and will cease to offer a fast track when demand exceeds that level and creates new backlogs.

For the rest of the world, reserved visas should not be significant. Department of State already waves up minority-country EB-5 applicants as soon as they’re ready by virtue of their nationality priority under the per-country limits, with no need for other priority. (I still expect to see quite a few minority-country rural investors, though, because the I-526 processing priority provision for rural in the new law does offer time advantage for everyone.)

Unused Reserved Visas: It’s hard to tell whether the “unused visas” provision in the new law is careless or crafty. Maybe it was written by people who just forgot all those conflicting parts of existing law that prevent EB-5 visas from rolling over to EB-5 from year to year. Maybe it was written by people who ignored the existing law conflicts on purpose, gambling that Department of State might choose to settle the conflict in favor of EB-5, start allowing a limited amount of EB-5 visa recapture for the first time in history, and start letting the EB-5 annual limit exceed its statutory maximum 7.1% of EB allocation for the first time. This could be a back door to recapturing at least FY2022’s large number of unused EB-5 visas, which would be very valuable. The darkest possible interpretation is that the “unused visa” provision was just put in the law to help ensure that no matter how interpreted – whether the unused set-aside visas are retained for new applicants or lost to other preference categories as usual — at least they’ll definitely not be generally available to the China backlog at each year-end, and thus conveniently serve to lengthen wait times for redeployable Chinese investment. I hope no one did think that way, because investors and their projects are not infinitely patient.

In the March 22 webinar, Oppenheim addressed questions about the unused visas provision in light of existing law.

[Quoted starting from minute 42] Oppenheim: In one way of looking at this, the INA guidelines clearly state how unused numbers within a preference category’s annual limit should be made available to other preferences. For example, Section 203(b)(1) indicates already that any unused employment fourth or fifth preference numbers should be added to the EB-1 annual limit. Also Section 201(c) says that any unused numbers from the previous year’s worldwide employment limit fall across and are to be used in the determination of the next year’s family sponsored annual limit. So, despite the fact there are these set aside provisions, I think it could be argued that the current year’s unused set-aside numbers could be made available to other EB-5 applicants, and then if they were still unused numbers under the overall EB-5 limit, such numbers could then fall up for potential use in EB-1 during the current fiscal year. And if you followed that logic, then the only numbers that ultimately remained unused after the fall-up provision would then fall across for the next year’s set-aside limit. That’s confusing, but I think that there’s room for interpretation, and it could be argued either way on this. …I think that there likely will be a need for technical corrections. … I do think that there potentially will be some changes, at least to the language to clearly identify what is meant. Because, for example on this set-aside provision where it’s saying, ok, if there are unused numbers under the 20 percent set-aside, that those numbers should be reserved and added to the next year’s limit. That is fine in regards to the EB-5 applicants, but if you’re an advocate for EB-1 or EB-2 or family fourth or any other preference category, you may be saying, well why can’t we have the same benefit where our unused EB-1 numbers are reserved for the next year, etc. That type of “reserved for the next year” previously has only occurred through legislative action to recapture unused numbers. So this is kind of a whole new world. And again, I think that’s why it’s going to be important to clearly interpret how you distinguish unused numbers.

[Quoted from minute 58] Joseph Barnett: Can I try to paraphrase what you mentioned before, Charlie, and let me know if I’m getting this right here. You think that the Department of State is going to have to create new visa categories to deal with the reserved visa classes. You don’t necessarily know how the existing investors are going to be included into those new visa categories without further action by investors or USCIS or some way to report that demand. And with regards to the unused visas provisions, there’s going to have to be some interpretation and discussion in DOS about how that’s going to play out and how it’s going to fall up or fall across – they’re just kind of unknowns at this point?

Oppenheim: Correct. [end Oppenheim quote]

Part 3: Data

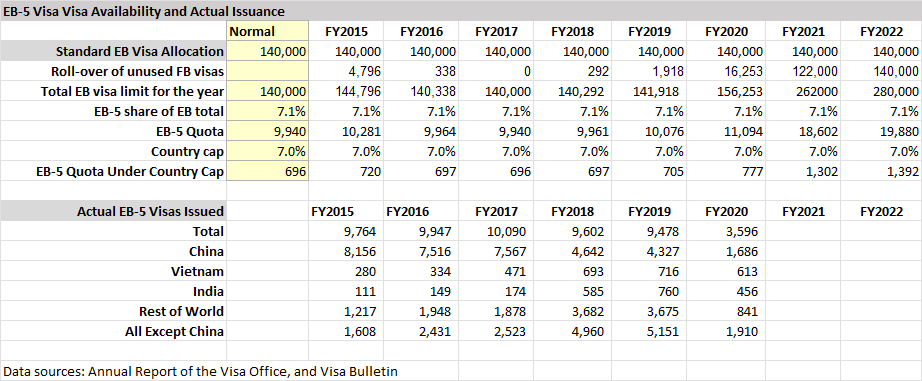

After all this general talk, let’s look at numbers. I’ve copied below tidy tables of figures that represent the individual real people caught up in all this, and the history of how EB-5 visa demand and allocation has played out to date. (To interact with the data and see source citations, access the Excel file of Key Backlog data linked to my EB-5 Timing page.)

Points to note as you look at visa issuance numbers:

- The variable number of EB-5 visas issued each year has followed from (1) the number of visas technically available to EB-5 and each country that year as calculated under the INA rules described above, and (2) the number of visas that applicants were practically able/willing to claim (by getting through I-526 processing to the visa stage) and that the government was practically able to issue (considering processing constraints).

- Note the number of EB-5 visas actually issued to China-born applicants each year, from over 8,000 in FY2015 to just over 4,000 in FY2018 and FY2019. Those China visa numbers were a function of visa demand from the rest of the world. Each year, the oldest applicants received whatever was leftover of the EB-5 limit after DOS satisfied rest-of-world demand within per-country limits. (Except FY2020, when everyone got constrained by COVID-19.)

On the following I-526 table, note the number and timing of I-526 filings from countries other than China. See that China had its I-526 filing surge early, which is why it now leads the standby queue at the visa stage, while India had a later surge that’s thus further back in queue priority (and largely not at the visa stage yet, thanks to sluggish I-526 processing). Most significant of all, note the relatively flat line of I-526 filings from non-backlogged countries since 2015, even during years of peak EB-5 popularity and the $500,000 threshold. EB-5 just doesn’t have a big market in most of the world. That “all except China, India, Vietnam” column in the I-526 filing trend gave hope to the China backlog and concern to people selling EB-5. Backlogged Chinese applicants could rejoice to see on-going low rest-of-world I-526 filing numbers, which underwrote the hope that “otherwise unused” visas would continue to be leftover from the rest of the world in significant numbers for the oldest Chinese applicants. Marketers would lament the persistently and organically low ROW I-526 numbers, and strategize to get more visas to offer the historically fruitful China/India/Vietnam markets now constrained by backlogs of old priority dates.

Part 4: Application

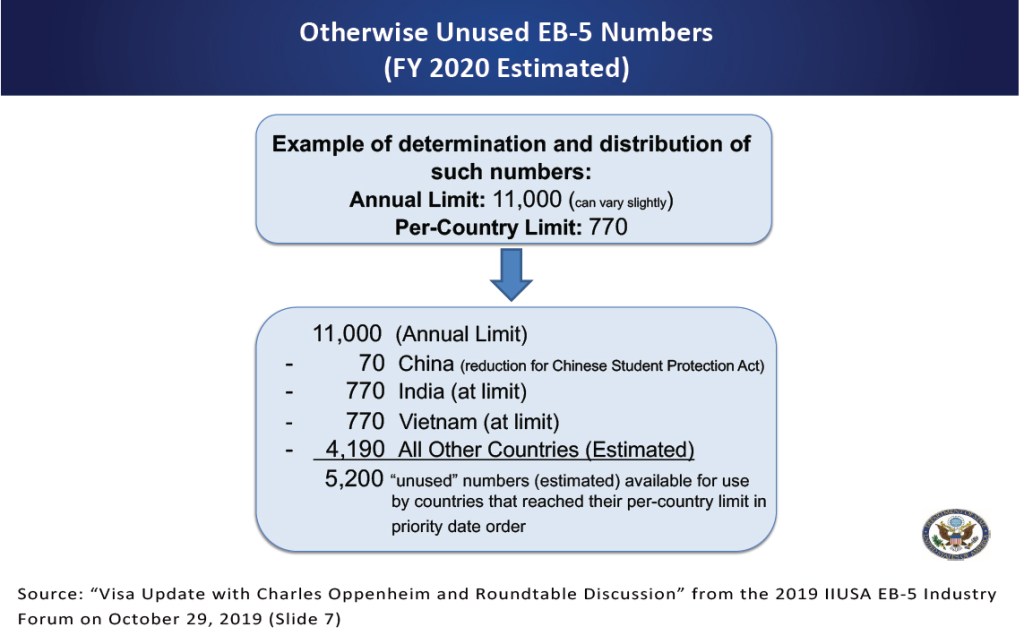

For a reminder of how EB-5 visa distribution used to work, consider this slide from the “Visa Update with Charles Oppenheim and Roundtable Discussion” at the 2019 IIUSA EB-5 Industry Forum (October 29, 2019). The equation starts with the annual visa limit, then deducts all qualified demand from applicants at/under the per-country limit, and ends with a difference of “unused” numbers available for allocation to the oldest applicants regardless of per-country limit.

As it turned out, a global pandemic intervened and prevented Department of State from actually issuing the number of visas anticipated for FY2020. But in theory, the 11,000 visa available for FY2020 should’ve been distributed first to all prepared applicants up to their 7% country limits, with the balance then leftover for the oldest i.e. Chinese applicants. Oppenheim estimated in 2019 that over 5,000 visa could be allocated to Chinese in FY2020, as a function of the expected number of “otherwise unused” numbers.

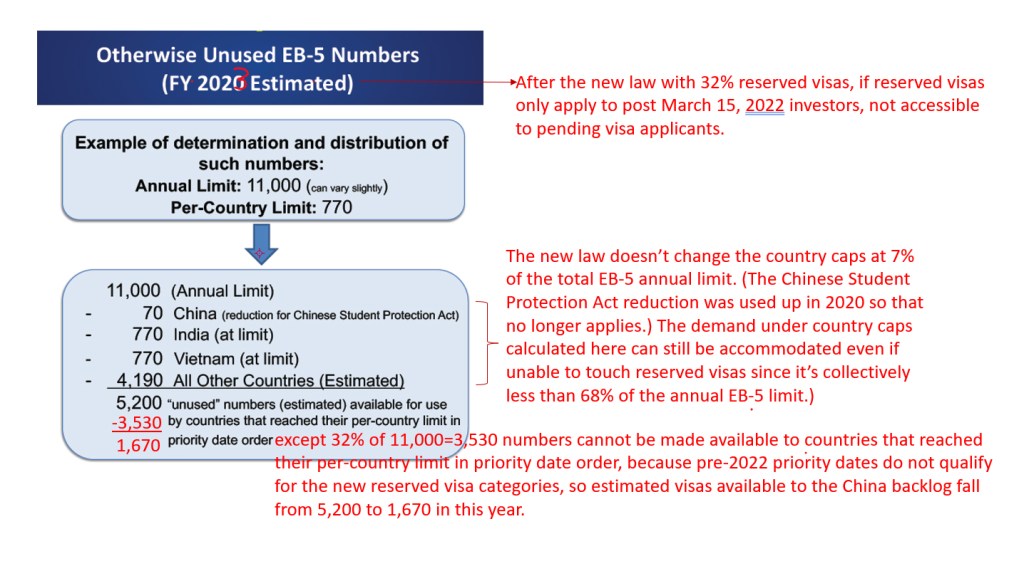

Now here’s a version of the same slide, but marked up to show how the calculation would change with reserved visas — if reserved visas are indeed reserved in new categories and not accessible to pending pre-March 2022 priority dates.

As illustrated, the difference falls on the “unused numbers” calculation. Removing 32% percent of visas from the general pool does not affect visa allocation under per-country limits in this year, because more than 32% of visas were going to be leftover after per-country allocation anyway. The impact is on the number of available leftovers for the oldest applicants, and the applicants depending on leftovers for their visa allocation. In the year shown in the slide example, the number of leftover visas for the oldest (Chinese) priority dates falls from 5,200 to 1,670.

Let’s say I’m a China-born EB-5 applicant who can estimate 40,000 other Chinese applicants in process with earlier priority dates. How does my wait time calculation change depending on whether I can estimate the queue before me proceeding at an average rate of 5,000+ visas per year to China, or 1,700 per year? 40,000/5,000=8 years. 40,000/1,700=24 years. That’s a huge difference. Of course, real life is complicated. For example 40,000 isn’t just a number but represents humans who are liable to giving up and aging out and dying, in increasing numbers as time goes on. So in real life, changing the denominator of a wait time equation – as reserved visas does for China – will change the numerator as well. In practice, if supply relief doesn’t bring down wait times, demand failure inevitably will. Meanwhile, a variety of factors besides reserved visas sway the denominator of the China wait time equation. Probably new minority-country investors who would’ve invested in EB-5 anyway will choose the new TEA categories, thus eventually blunting the marginal-difference impact of set-asides. Probably overall demand at the $800,000+ level will be lower than before, such that lower incoming demand will leave more visas unused and available to the China backlog eventually even above set-aside limits. Maybe the backlog will get some supply relief in three years if DOS actually allows recapturing unused reserve visas. Real life gives many moving parts to account for. But, all other factors being equal, reserved visas in themselves (if genuinely reserved) certainly have a dreadful impact on the wait time equation for backlogged Chinese applicants. (For detailed analysis, see EB5 Sir’s recent posts.)

Part 5: Conclusion

Anyone who made it to the end of this exhausting article obviously cares about the impact of reserved visas. What can we do now? The EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022 is law since March 15, 2022. Is there any room to stand athwart history yelling Stop?

Here are some theoretical possibilities for making the reserve visas law turn out less bad for our past clients than it could be.

- The China backlog will lose at least 1,000 fewer annual visas than it would lose otherwise if (A) Department of State interprets the new reserved visa categories as being available theory to pending applicants who happen to have invested in high unemployment area, rural area, or infrastructure projects, and also (B) DOS and USCIS communicate to mark pending applications that match the new set-aside categories.

- The China backlog will lose fewer visas if Department of State interprets the “unused visas” provision in the law to mean that 32% of the visas that will go unused in FY2022 (6,362 numbers) can be added to the EB-5 limit in FY2024, and generally available.

- The China backlog will lose fewer visas if Department of State disregards the “unused visas” provision in the new law as contradictory to the INA, and makes any unused EB-5 visas available to the oldest EB-5 priority dates at the end of each year, regardless of reserved status.

- The China backlog may lose fewer visas if we decline to promote reserve visas to new Chinese, Indian and Vietnamese clients, realizing that every one EB-5 visa taken to accommodate a new backlog-country client who wouldn’t have invested otherwise is one visa removed from the pool that would have been available to the oldest backlogged priority dates if not for visa reserves. But this grand gesture would only help our past clients if unused reserved visas can indeed eventually be accessed by the backlog – an open question.

- Investors and project companies can best manage impacts if they are realistic about what’s happening. Let’s refuse fallacies (“this is queue cutting with no queue cuts”) and cop-outs (“it’s complicated, so don’t bother thinking or worrying about it”)

- Most important, we need to pour advocacy dollars and energy into getting any possible backlog relief for the oldest EB-5 applicants, who need it now more desperately than ever. Regional centers who don’t want to deal with a fight for the exits will want to help fight for visa conditions that keep immigration hopes alive. The best way to incentivize new EB-5 demand is to create an environment where past EB-5 users can also be seen to flourish.

Discover more from EB-5 Updates

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Dear Suzanne,

Another very thorough analysis from your side! Thank you for this- it is a very hot topic.

I wanted to check if one has already applied for an EB5 under the new TEA definition under the rural $900k category, would the priority be valid for such applicants. The logic is that the definition of the TEA has not changed, and the payment is more than the new amount, therefore such applicants (post Oct 2019, applied under the new Rural TEA definition) should benefit. If we are already meeting the standards, even though we are not new applicants why would we be penalized.

Your thoughts on the same?

Thanks

See the “Law” section of my post for all I can say on this important question. (Including quotes from Charles Oppenheim last week.)

Hi Suzanne, thank you for your wonderful analysis. What would happen to Koreans who have been under 7% cap but above sustainable level on i-526? I filed i-526 in Sep 2019 and now wondering if i can get it approved by Nov 22 as USCIS posted they are targeting 6 months for i-526. Does May 15th 2022 + 6 months = Nov 2022 i-526 approval seems reasonable to you?

For a Korean with September 2019 priority date, the major constraint is not visa availability but USCIS I-526 processing capacity and productivity. I’m happy to see that USCIS posted a goal of lowered processing times. But the current facts are (1) an I-526 inventory of 13,000+ forms (of which 10,000+ were likely filed before Sept 2019), and (2) I-526 productivity less than 300 completions per month for most of the last three years (and only 20 completions per month in the most recent quarter). With that starting point, the I-526 inventory could hardly be cleared in six months from now, and 6-month processing targets will take time to achieve. If all Koreans with pending I-526 got approved and sent to the National Visa Center at once, then they would have a visa-stage wait. So long as slow I-526 processing already distributes Korean applicants over time, you might avoid additional wait at the visa stage.

Hi Suzanne, Visa availability for Indian investors is current for some time now. Is it expected to change in next 12 months. What is the expected priority date if wait is introduced again ? Any insight would be greatly appreciated.

In my post, you can look at the I-526 table to see the number of Indian I-526 filings, calculate the number of visa applications likely to result from those filings, and divide by 700 to estimate the time it will take to assign visas to all those applicants. India has been current in the visa bulletin because most I-526 filed since 2018 are still pending at USCIS, and the visa bulletin can only recognize applicants qualified at the visa stage, not I-526 demand. The question of when the visa bulletin changes for India, and to what date, depends on the rate at which USCIS approves Indian I-526, and the order in which USCIS approves them. I don’t expect any visa bulletin changes for India in FY2022, which has more visas than consulates and USCIS can possibly issue regardless of demand. (Except maybe a date for filing, if the visa bulletin reacts to a large volume of newly-possible concurrent I-485 filings.) I do expect final action dates and dates for filing for India in FY2023, unless USCIS continues so unproductive Indian applicants can’t reach the visa stage in sufficient volume to max out India visa availability in FY2023.

Hi Suzanne, Another great analysis! Thank you for being so thorough in your work. What are your thoughts on concurrent filing of I-526 & I-485 & I-765? I have a pending I-526 (Oct 2018 PD). Will I be able to file I-485 while my I-526 is pending? If yes, when do you think USCIS will start accepting it? Thank you.

So far I’ve heard three reports from people with pending I-526 (direct EB-5) who already attempted concurrent I-485 filing. Two were rejected by the lockbox mailroom, and one was accepted. The guy whose filing was accepted said that he added a cover letter highlighting the new law that allows concurrent filing for EB-5.

Thank you for info Suzanne! Mine is thru RC and visa is currently available for my country of birth (Taiwan).

Hi Suzanne,

As always, great analysis. Hope all is well. Well, we are all back in business and wading through the mess of this new legislation, but it beats the alternative. I have a question for you. In your opinion, how would removing the country caps (which is going to be proposed again) interplay/impact the additional wait times likely to result from the new set-asides (depending on how USCIS applies them) to investors from China, India, and Vietnam currently waiting for visas?

Thanks!

Lulu Gordon EB5 Capital Senior Vice President / General Counsel

Tel: (240) 713-3119 | Mobile: (415) 317-4477 lgordon@eb5capital.com | http://www.eb5capital.com

That is such an important question. To try to answer it, I take the I-526 receipt numbers in my post and turn them into an estimated breakdown of the current visa backlog by year of priority date. (I assumed 75% survival rate, historical family size ratios, that most priority dates since FY2018 are still pending considering I-526 processing times and low visa issuance, and that at least FY15 Q4 and later China applicants are still pending, considering the visa bulletin.) Removing country caps would simply make visa issuance chronological by priority date, so I calculated cumulative total applicants by year. Then I divided by annual visa availability assuming two scenarios — with and without 32% exclusively reserved visas. Here’s a table of the calculation: https://ebfive.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/scenario.jpg The bottom line is that removing country caps would yield better wait times for all China priority dates, The change would be about neutral for India/Vietnam FY2019 and later dates, if not for reserved visas. But even with reserved visas, India would add just a few years on top of already-long visa wait expectations. The painful impact would be for pending applicants from all other countries, since they’d find their recent priority dates suddenly at the end of an 8-12-year line. A fairness argument would probably side with the minority-country applicants, considering their reasonable expectations based on the rules when they filed. A “greatest good for the greatest number” argument would have to side with removing country caps, since the Chinese applicants who would benefit represent 71% of the EB-5 backlog.

Hi Suzanne,

Thanks as always for the detailed post.

I am not sure about the wait/processing time in the case where one has an approved I-526, paid the fees at the NVC, and got an email from them stating that they have received all the requested documentation and is in queue for interview appointment overseas. This is as of June 2021. What is the processing time likely to be in this case as per your estimate?

Thanks very much.

Arun

Greetings!

Pursuant to the recently passed EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022, we are expecting EB-5 Regional Centers to start filing new I-526 petitions on our about May 15, 2022.

Furthermore, USCIS will resume adjudicating regional center program petitions and applications, and the Department of State (including National Visa Center-NVC) will resume processing, scheduling, and issuing Regional Center-affiliated EB-5 visas.

Thank you Kumar.

What is the source of the information, especially the latter part ? Hope it’s not just a sales pitch. We are aware about the first part but there is no clarity on the second part.

Pingback: EB-5 Visa Availability for the May 2022 Visa Bulletin and Reservations on Reserved Visas-Skipping the Waiting Line is Un-American - WR Immigration

Pingback: The EB-5 Visa Backlog Problem - American Immigrant Investor Alliance